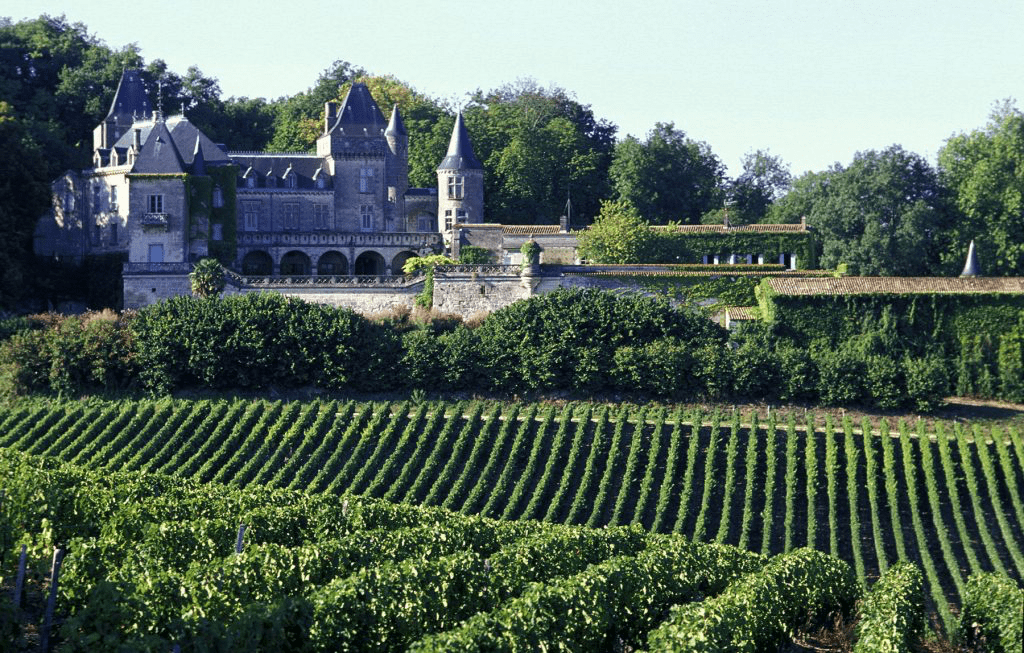

Bordeaux, in southern France, is one of, if not the world’s most famous wine region, steeped in long-standing excellence and tradition through closely controlled grape varietals and farming techniques for each appellation that have been in place for over eighty years.

As far as I can remember, the iconic Bordeaux red blends have been either Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot dominant, supported by Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carménère.

Two experimental plots named VitAdap and GreffAdapt, have been established to study the impacts of climate change on proposed and current varietals including the effects of water stress.

Malbec has been the grape most challenged by climate change and its use in the region has diminished significantly while Petit Verdot is experiencing a resurgence and plantings have increased nearly two-hundred percent

Two-thirds of the red vines planted in Bordeaux are merlot that for centuries has benefited from the local climate to reach peak ripeness. Although still the premier Bordeaux red varietal, merlot is being scrutinized as a potential future victim of rising temperatures.

The current white varietals are dominated by Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc with support from lesser known grapes like Sauvignon Gris, Muscadelle, Colombard, Ugni Blanc, Merlot Blanc and Mauzac.

In the past months, Bordeaux has garnered worldwide attention from a recent report outlining a series of actions taken to adapt to the growing impacts of climate change. Since research on the impacts of climatology was first conducted in 2003 by the Bordeaux Wine Council (CIVB), it has been a major focus in future planning, specifically the changes in climate, its impact to oneology and the use of plant material(varietal selection). The Council has spent nearly €2 million over the past decade on environmental research.

Recently the Bordeaux AOC and Bordeaux Supérieur winemakers approved new “grape varieties of interest” as part of a continuing plan to adapt to the impacts of climate. The list includes varietals new to the region as well as some nearly forgotten and now making a comeback. The new experimental “grapes of interest” are mostly late-ripening to better assimilate with the established harvest framework, less susceptible to rot and intended to satisfy aromatic losses due to hotter weather.

Among the red varietals to be approved for planting include Arinarnoa, a cross between Tannat and Cabernet Sauvignon and Touriga Nacional, a popular red grape from the Douro Valley in Portugal, used in their fine ports and still wine blends. Also included are Marselan, a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache (sounds delicious)and the long-forgotten Bordeaux varietal, Castets, both known for their resistance to rot and suitability for aging.

The newly approved white “grapes of interest” include Alvarinho, another Portuguese varietal that has gained popularity in the United States, Liliorita, a cross between baroque and chardonnay and the late-ripening Petit Manseng, all highly aromatic.

These changes are subject to approval by the Institut national de l’origine et de la qualité (INAO),a French organization charged with regulating agricultural products, and come with conditions. The “grapes of interest” must be listed as secondary and be limited to five percent of the planted vineyard area. They cannot exceed ten percent of the final blend and their use is only authorized for a ten year period subject to one renewal.

In addition to their research on climate change and sustainability, the Bordeaux wine industry set out for the first time, a decade ago, to assess its carbon footprint that was determined to be 840,000 tons CO2 equivalent, stemming mostly from materials and products, freight and energy. As a result, they committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the development of the Climate Plan 2020, a roadmap that was shared with the entire wine industry. The plan set goals of twenty percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, twenty percent reduction in energy use, a twenty percent increase in renewable energy and a twenty percent decrease in water use.

A follow-up assessment in 2013 revealed a nine percent decrease in the wine trade’s carbon footprint within five years.

The real story here is that climate change represents multiple challenges for the agricultural industry and when a premier wine growing region begins to reassess engrained traditional practices, people pay attention. Clearly, Bordeaux’s long-term plan will be implemented methodically with strategies designed to maintain their position as an elder statesman and global giant. However, they must be credited for providing the insight and leadership that will benefit everyone.

Leave a comment